I have a thing about financial market quotes at the moment. Here are a couple of my favourite ones:

"Those who already own a house are only mildly concerned by the modest falls in the value of their homes, after all, the value of their property has practically doubled in the last six years. However many are already questioning whether this is the time to sell, and whether they shouldn't hang on until the market resumes its normal upward trend."

Grainne Gilmore, The Times economics correspondent

"The trend is no longer your friend"

Michael Turvey, INVESTools

Why would anyone buy the obligations of a shaky deficit-ridden political system in a currency that appears fundamentally unsound?

Martin Hutchinson, the Bear's Lair

“The repricing of risk…is not a process that we should try to reverse.”

Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England

"Up until this point in time, the market and the regulators have had to rely on the bond insurers and the rating agencies to calculate their own losses in what we deem a self-graded exam. Now the market will have the opportunity to do its own analysis.''

William Ackman, managing partner of Pershing Square Capital Management.

"Inflation is a regressive tax. Whether you earn less than $30,000 or more than $300,000, you spend about the same on gasoline, but at $30,000 a year an extra $375 is close to 2 percent of your entire after tax income."

FRED, iTulip Administrator

Am I Mr. Brightside? No, I believe that subprime's awful, even worse than the bears think.

Jim Cramer

Thursday, 31 January 2008

How wrong can you be? Take a look at this article and you might get some idea.

Two years ago, Businessweek wrote article arguing that the US housing bubble will not burst. Well, we know what happened since then. The housing data has been just appalling; prices are falling in virtually every city, home starts are down, and sales volumes have tanked. However, the most shocking number must be the one for foreclosures; at the moment, one house in a hundred in the US is in some form of repossession process.

Of course, we find the same kind of deluded "the bubble can't burst" thinking here in the UK. Far too many people have too much faith in the property market. While the reality of an overpriced, over-inflated market is starting to impose itself, the majority of UK homedebtors are in denial.

Anyway, here is the article; read it and weep.

Why The Housing Bubble Won't Burst

Type the words "falling housing prices" into Google and more than 8 million citations pop up. Michael Youngblood's name won't be among them. Despite all the fear that single-family home prices will decline, the managing director of asset-backed securities research at Friedman Billings Ramsey & Co. (FBR ) in Arlington, Va., thinks residential real estate is a lot stronger than most people suspect. He bases this assessment on a new economic model he created that forecasts housing prices in 379 metropolitan statistical areas. Associate Editor Toddi Gutner spoke with Youngblood about his upbeat view and his surprising prediction that the greatest price appreciation will be coming in so-called bubble markets.

What makes you more optimistic than other housing experts?

I look at two economic indicators that I think drive the housing market: the growth in employment and the growth in personal income. Getting a job or a salary increase is what motivates people to buy their own home. This is different from the data the National Association of Realtors and other organizations rely on. They are more concerned with technical indicators such as the inventory-to-sales ratio and the number of months a house is on the market. These aren't leading indicators. Instead, they move with current changes in the market, rather than predict those changes.

Do you think the housing bubble argument is overblown?

Absolutely. It's overblown because there is no national housing market, so there can't be a national house-price bubble. However, there are bubbles in 75 of the 379 markets I studied. A bubble exists when the ratio of the median existing house price to per capita personal income exceeds 6.8 times. This definition is based on historical data of when other markets, like Houston and Boston, had bubbles.

Where are the bubbles?

Most of the bubbles exist on the East and West coasts in such markets as New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, Phoenix, Honolulu, and Tacoma, Wash. Only 12 of the 75 cities are located inland: Boulder, Colo., Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, Flagstaff, Ariz., and Las Vegas among them.

What markets are likely to show the biggest price gains and declines this year?

We expect the greatest gains in Bakersfield, Calif. (43%), Fort Myers, Fla. (42%), Stockton, Calif. (39%), and Punta Gorda, Fla. (35%); the biggest declines in Harrisburg, Pa. (8%), Odessa, Tex., Roanoke, Va., and Utica, N.Y. (all 6%).

But most people think that Florida and California are overpriced. Why would markets there show the greatest gains?

There is clearly speculation taking place in these areas. But bubbles can persist for very long periods of time, and it typically requires a downturn in the local economies to burst them. Then they can deflate for a long time, too. Given the expected gains in employment and income in both states, I don't expect the housing prices to fall in 2006.

How can investors play this information?

Investors should not necessarily fear homebuilders who are operating in bubble markets. House prices don't plunge immediately in economic downturns the way stock prices do. There is typically a one-year lag after the local economy sees a decline in average employment and income. Thus, the homebuilder stocks may continue to perform well for a while longer.

Of course, we find the same kind of deluded "the bubble can't burst" thinking here in the UK. Far too many people have too much faith in the property market. While the reality of an overpriced, over-inflated market is starting to impose itself, the majority of UK homedebtors are in denial.

Anyway, here is the article; read it and weep.

Why The Housing Bubble Won't Burst

Type the words "falling housing prices" into Google and more than 8 million citations pop up. Michael Youngblood's name won't be among them. Despite all the fear that single-family home prices will decline, the managing director of asset-backed securities research at Friedman Billings Ramsey & Co. (FBR ) in Arlington, Va., thinks residential real estate is a lot stronger than most people suspect. He bases this assessment on a new economic model he created that forecasts housing prices in 379 metropolitan statistical areas. Associate Editor Toddi Gutner spoke with Youngblood about his upbeat view and his surprising prediction that the greatest price appreciation will be coming in so-called bubble markets.

What makes you more optimistic than other housing experts?

I look at two economic indicators that I think drive the housing market: the growth in employment and the growth in personal income. Getting a job or a salary increase is what motivates people to buy their own home. This is different from the data the National Association of Realtors and other organizations rely on. They are more concerned with technical indicators such as the inventory-to-sales ratio and the number of months a house is on the market. These aren't leading indicators. Instead, they move with current changes in the market, rather than predict those changes.

Do you think the housing bubble argument is overblown?

Absolutely. It's overblown because there is no national housing market, so there can't be a national house-price bubble. However, there are bubbles in 75 of the 379 markets I studied. A bubble exists when the ratio of the median existing house price to per capita personal income exceeds 6.8 times. This definition is based on historical data of when other markets, like Houston and Boston, had bubbles.

Where are the bubbles?

Most of the bubbles exist on the East and West coasts in such markets as New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, Phoenix, Honolulu, and Tacoma, Wash. Only 12 of the 75 cities are located inland: Boulder, Colo., Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, Flagstaff, Ariz., and Las Vegas among them.

What markets are likely to show the biggest price gains and declines this year?

We expect the greatest gains in Bakersfield, Calif. (43%), Fort Myers, Fla. (42%), Stockton, Calif. (39%), and Punta Gorda, Fla. (35%); the biggest declines in Harrisburg, Pa. (8%), Odessa, Tex., Roanoke, Va., and Utica, N.Y. (all 6%).

But most people think that Florida and California are overpriced. Why would markets there show the greatest gains?

There is clearly speculation taking place in these areas. But bubbles can persist for very long periods of time, and it typically requires a downturn in the local economies to burst them. Then they can deflate for a long time, too. Given the expected gains in employment and income in both states, I don't expect the housing prices to fall in 2006.

How can investors play this information?

Investors should not necessarily fear homebuilders who are operating in bubble markets. House prices don't plunge immediately in economic downturns the way stock prices do. There is typically a one-year lag after the local economy sees a decline in average employment and income. Thus, the homebuilder stocks may continue to perform well for a while longer.

Wednesday, 30 January 2008

Making sense out of the FSA

The Financial Services Agency has just published their Financial Risk Survey for 2008. As you would expect, the report is full of obtuse, convoluted phrases. Such reports leave the reader bewildered and confused about potential risks. The purpose is, afterall, not to enlighten but to obscure the dangers.

Today, I had too much time on my hands. I actually sat down and read this report. I have chosen my ten favourite lines and decoded them in the vain hope that we can all have a slightly better understanding of financial sector vulnerabilities going forward.

1. The recent tightening in financial conditions may have exposed some firms’ business models as being potentially unsuitable in more stressed financial conditions where, for example, access to liquidity is restricted.

The banks have taken on way too much risk. Now the banks are struggling to get cash.

2. The structured finance vehicles that some firms have chosen to use over the last few years have had a material impact on their financial performance during stressed financial market conditions.

The banks have been producing new financial products that we could not understand. It turns out that the banks didn’t understand them either.

3. Despite the more difficult economic and financial conditions, firms must not divert attention away from focusing on conduct-of-business requirements and our high-level principles.

The FSA better watch the banks more closely because they seriously starting to misbehave.

4. Market participants and consumers may lose confidence in financial institutions and in the authorities’ ability to safeguard the financial system.

The FSA can not afford to screw up like it did with Northern Rock.

5. Financial market conditions weakened considerably in 2007 as investors reassessed risks in their portfolios and risk premia began to rise.

The sub prime crap hit the fan in August, and now everyone is running for cover.

6. Tighter credit conditions are likely to add further risks to the growth outlook as consumers’ ability to spend and finance their house purchases comes under pressure.

The UK housing market is going to crash and it will take the economy down with it.

7. If consumers found it increasingly difficult to obtain credit, the number of property transactions would be likely to fall and the market for mortgages for own-house purchase would therefore become smaller. However, the demand for re-mortgaging and second charge lending could rise, particularly as consumers consolidate debt.

When it crashes, consumers are going to try to keep on borrowing, digging themselves into an even bigger hole. They are addicted to debt and there is nothing anyone can do to save them.

8. As commercial and residential property prices fall, financial firms with high concentrations in this type of lending could face losses which require an increase in provisions on both the residential and commercial property books, thus reducing profitability. This could put firms’ capital under pressure.

When the market crashes, the banks will be in serious difficulties. Some of them might go down the same hole that Northern Rock is now exploring.

9. Banks and other lending institutions might need to increase their provisions to account for consumers having difficulties in repaying their mortgages and unsecured loans due to a fall in their disposable and real incomes. However, changes in interest rates would give financial firms greater opportunities to widen margins to maintain profitability.

Please send a memo to the MPC begging them to cut rates. Many households are about to stop paying their debts. The banks are in trouble and if rates don’t come down, banks won’t be able to make enough money to cover the losses.

10. Over the course of 2007 there was a transition from a situation where there was overconfidence in the market to the current situation where confidence is low.

The FSA have failed miserably to prevent a financial crisis. While it may be our fault, we will push the blame onto overconfidence. As far as we know, overconfidence has absconded, and he won't be coming back any time soon.

Today, I had too much time on my hands. I actually sat down and read this report. I have chosen my ten favourite lines and decoded them in the vain hope that we can all have a slightly better understanding of financial sector vulnerabilities going forward.

1. The recent tightening in financial conditions may have exposed some firms’ business models as being potentially unsuitable in more stressed financial conditions where, for example, access to liquidity is restricted.

The banks have taken on way too much risk. Now the banks are struggling to get cash.

2. The structured finance vehicles that some firms have chosen to use over the last few years have had a material impact on their financial performance during stressed financial market conditions.

The banks have been producing new financial products that we could not understand. It turns out that the banks didn’t understand them either.

3. Despite the more difficult economic and financial conditions, firms must not divert attention away from focusing on conduct-of-business requirements and our high-level principles.

The FSA better watch the banks more closely because they seriously starting to misbehave.

4. Market participants and consumers may lose confidence in financial institutions and in the authorities’ ability to safeguard the financial system.

The FSA can not afford to screw up like it did with Northern Rock.

5. Financial market conditions weakened considerably in 2007 as investors reassessed risks in their portfolios and risk premia began to rise.

The sub prime crap hit the fan in August, and now everyone is running for cover.

6. Tighter credit conditions are likely to add further risks to the growth outlook as consumers’ ability to spend and finance their house purchases comes under pressure.

The UK housing market is going to crash and it will take the economy down with it.

7. If consumers found it increasingly difficult to obtain credit, the number of property transactions would be likely to fall and the market for mortgages for own-house purchase would therefore become smaller. However, the demand for re-mortgaging and second charge lending could rise, particularly as consumers consolidate debt.

When it crashes, consumers are going to try to keep on borrowing, digging themselves into an even bigger hole. They are addicted to debt and there is nothing anyone can do to save them.

8. As commercial and residential property prices fall, financial firms with high concentrations in this type of lending could face losses which require an increase in provisions on both the residential and commercial property books, thus reducing profitability. This could put firms’ capital under pressure.

When the market crashes, the banks will be in serious difficulties. Some of them might go down the same hole that Northern Rock is now exploring.

9. Banks and other lending institutions might need to increase their provisions to account for consumers having difficulties in repaying their mortgages and unsecured loans due to a fall in their disposable and real incomes. However, changes in interest rates would give financial firms greater opportunities to widen margins to maintain profitability.

Please send a memo to the MPC begging them to cut rates. Many households are about to stop paying their debts. The banks are in trouble and if rates don’t come down, banks won’t be able to make enough money to cover the losses.

10. Over the course of 2007 there was a transition from a situation where there was overconfidence in the market to the current situation where confidence is low.

The FSA have failed miserably to prevent a financial crisis. While it may be our fault, we will push the blame onto overconfidence. As far as we know, overconfidence has absconded, and he won't be coming back any time soon.

Mortgage approvals come crashing down.

UK mortgage approvals are crashing like a stone. In December, approvals fell to their lowest level since 1995.

According to the Bank of England, just 73,000 house purchase loans were approved. The average approval rate during the first half of 2007 was around 100,000 a month.

Let is repeat the golden rule of real estate:

"Credit availability determines house prices"

No credit growth, no house price growth.

According to the Bank of England, just 73,000 house purchase loans were approved. The average approval rate during the first half of 2007 was around 100,000 a month.

Let is repeat the golden rule of real estate:

"Credit availability determines house prices"

No credit growth, no house price growth.

Losing big

Which bank will come top of the table of sub prime losers.

Today, UBS put down a very strong claim. Today, it announced a further $4 billion of losses, bringing its total sub prime losses to around $18 billion. This unprecedented losses should come as no surprise. At one point last year, the bank held about $40 billion of sub prime related debt.

With losses of this magnitude, the bank's capital is disappearing fast. The FT reported that UBS's "BIS Tier I capital ratio – a key measure of its financial strength – amounted to 8.8 per cent at the end of December." It went on to say that 8.8 per cent was "well below the 11-12 per cent ratio the bank has as its goal." If this capital ratio falls below 8 percent, then the bank would be in serious trouble with financial regulators.

With this in mind, UBS are frantically looking around for extra capital. Anyone out there interested in bailing out UBS?

Today, UBS put down a very strong claim. Today, it announced a further $4 billion of losses, bringing its total sub prime losses to around $18 billion. This unprecedented losses should come as no surprise. At one point last year, the bank held about $40 billion of sub prime related debt.

With losses of this magnitude, the bank's capital is disappearing fast. The FT reported that UBS's "BIS Tier I capital ratio – a key measure of its financial strength – amounted to 8.8 per cent at the end of December." It went on to say that 8.8 per cent was "well below the 11-12 per cent ratio the bank has as its goal." If this capital ratio falls below 8 percent, then the bank would be in serious trouble with financial regulators.

With this in mind, UBS are frantically looking around for extra capital. Anyone out there interested in bailing out UBS?

Tuesday, 29 January 2008

It is different this time

Why did the UK housing prices reach the extraordinary levels we see today? There is no shortage of answers to this question, but whatever the explanation, it invariably begins with those five fatal words - "it is different this time".

Some pointed to demographics; the nuclear family was breaking down, creating an army of lonely single home buyers. As this army expanded, housing demand increased. Others suggested that the huge number of migrants coming into the country put unbearable pressure on the market, and likewise pushed up prices.

There was a variation on this theme, which pointed to the endless number of wealthy rootless cosmopolitans, who came to London and bought up huge swathes of property, with only a casual glance at the prices.

Structural factors was another favourite. The UK's archaic planning laws was a well-worn argument, while the peace dividend in Northern Ireland provided a regional flavour to the "it is different this time" mantra.

Whatever the explanation, the conclusion was always the same; conventional methods for determining home valuations no longer applied to the housing market. There was no point looking at affordability indicators or price-to-income ratios. The UK had "changed fundamentally" during the last ten years, and this "change" was reflected in property prices.

Superficially, the "it is different this time" claim must be correct. Obviously, when prices are racing ahead at 20 percent a year, something very strange and unusual must be happening somewhere. The curious thing, however, is why people prefer to accept a convoluted explanation, when a simple and convincing one is ignored. There was something wonderful and magical about how a grotty little terrace house in, say Fulham, could into multi-million pound money making machine. This magic needs a magical explanation.

Unfortunately, the answer to this transformation was obvious to anyone who wanted an honest explanation for the housing bubble. A casual visit to the Bank of England's online statistical database provided the answer. It has been credit that has driven the beast. The banks have gone on a lending binge. Households have met the banks halfway, happily absorbing the huge quantities of debt that have recklessly poured into the housing market.

The English language strains to provide a vocabulary that can describe this growth of credit. To say that lending standards were lax does not come close to describing the myopic decision-making process in banks. Describing the stock of outstanding debt as huge, somehow misses the intrinsic irresponsibility of piling on debt without any thought of how it would be repaid. However, let us give our limited vocabulary free rein; this huge outstanding debt stock arose from a voluminous, gargantuan, historically unprecedented borrowing binge that has endangered the financial well-being of the UK economy.

Whatever we may have thought in the past, today, the phrase "it is different this time" is taking on a new and frankly terrifying meaning. The UK, along with large parts of the industrialized world, now face a financial catastrophe. Disaster beckons, judgment day approaches and the UK economy must now answer for its transgressions.

To calibrate just how bad things are, go back 12 months to January 2007. Suppose somebody said that within the next 12 months there would be run on a major UK bank; that a rogue trader would lose a French bank some $7 billion; that virtually every major investment banks would own up to billions of dollars of losses, requiring them to run around the world, cap in hand, looking for new funds to recover their lost capital. Would you have believed any of this? As we all know, these few examples are but a sample of the financial shocks that are being uncovered almost daily.

Things are different today; and with this change, comes new darker consequences. Property prices are sliding, recent data has established this as a fact. As they slip, all those childish illusions about easy money evaporate. All that will be left will be those debt contracts, which were so easy to sign, but will yet prove to be so painful to honour.

Here, we find something constant and unchanging. Debts must be repaid, or the debtor must default and accept financial ruin. Today, UK households are beginning to appreciate this crushing stability of debt. Bubbles may come and go, and with them, our pathetic illusions, but the debts, they stay until they are repaid in full.

Some pointed to demographics; the nuclear family was breaking down, creating an army of lonely single home buyers. As this army expanded, housing demand increased. Others suggested that the huge number of migrants coming into the country put unbearable pressure on the market, and likewise pushed up prices.

There was a variation on this theme, which pointed to the endless number of wealthy rootless cosmopolitans, who came to London and bought up huge swathes of property, with only a casual glance at the prices.

Structural factors was another favourite. The UK's archaic planning laws was a well-worn argument, while the peace dividend in Northern Ireland provided a regional flavour to the "it is different this time" mantra.

Whatever the explanation, the conclusion was always the same; conventional methods for determining home valuations no longer applied to the housing market. There was no point looking at affordability indicators or price-to-income ratios. The UK had "changed fundamentally" during the last ten years, and this "change" was reflected in property prices.

Superficially, the "it is different this time" claim must be correct. Obviously, when prices are racing ahead at 20 percent a year, something very strange and unusual must be happening somewhere. The curious thing, however, is why people prefer to accept a convoluted explanation, when a simple and convincing one is ignored. There was something wonderful and magical about how a grotty little terrace house in, say Fulham, could into multi-million pound money making machine. This magic needs a magical explanation.

Unfortunately, the answer to this transformation was obvious to anyone who wanted an honest explanation for the housing bubble. A casual visit to the Bank of England's online statistical database provided the answer. It has been credit that has driven the beast. The banks have gone on a lending binge. Households have met the banks halfway, happily absorbing the huge quantities of debt that have recklessly poured into the housing market.

The English language strains to provide a vocabulary that can describe this growth of credit. To say that lending standards were lax does not come close to describing the myopic decision-making process in banks. Describing the stock of outstanding debt as huge, somehow misses the intrinsic irresponsibility of piling on debt without any thought of how it would be repaid. However, let us give our limited vocabulary free rein; this huge outstanding debt stock arose from a voluminous, gargantuan, historically unprecedented borrowing binge that has endangered the financial well-being of the UK economy.

Whatever we may have thought in the past, today, the phrase "it is different this time" is taking on a new and frankly terrifying meaning. The UK, along with large parts of the industrialized world, now face a financial catastrophe. Disaster beckons, judgment day approaches and the UK economy must now answer for its transgressions.

To calibrate just how bad things are, go back 12 months to January 2007. Suppose somebody said that within the next 12 months there would be run on a major UK bank; that a rogue trader would lose a French bank some $7 billion; that virtually every major investment banks would own up to billions of dollars of losses, requiring them to run around the world, cap in hand, looking for new funds to recover their lost capital. Would you have believed any of this? As we all know, these few examples are but a sample of the financial shocks that are being uncovered almost daily.

Things are different today; and with this change, comes new darker consequences. Property prices are sliding, recent data has established this as a fact. As they slip, all those childish illusions about easy money evaporate. All that will be left will be those debt contracts, which were so easy to sign, but will yet prove to be so painful to honour.

Here, we find something constant and unchanging. Debts must be repaid, or the debtor must default and accept financial ruin. Today, UK households are beginning to appreciate this crushing stability of debt. Bubbles may come and go, and with them, our pathetic illusions, but the debts, they stay until they are repaid in full.

Monday, 28 January 2008

The debt industrial complex

Stop sending me credit card letters, man.....

For those with broadband....

The shakeout begins

It is never nice to hear about job losses. U.S. investment bank Goldman Sachs plans to fire about 5 percent of its global workforce in coming months after its annual staff evaluation.

The New York-based bank said those being dismissed will be the "worst-performing employees". However, what does that mean in an industry that has generated billions of pounds of losses?

A post bubble world

"We are living in a post-bubble world, following the stock market bubble of the 1990s and the real estate bubble of the 2000s. That is the backdrop for the current crisis. We need to restore confidence in the markets’ basic ability to function, not in their presumed tendency to make us all rich by always going up. "

Robert Shiller, professor of economics and finance at Yale

House prices - it is four in a row

The housing data is in for December, and prices are down for a fourth consecutive month. In many respects, the housing crash is a process of aclimatisation. Just as the bubble was marked by years of double digit growth, we must now learn to accept that prices will continue to fall for the foreseeable future.

So what happened in December? According to Hometrack, the average cost of a home in England and Wales fell by 0.3 percent. After 12 months of those kinds of monthly declines, prices would be down around 3.6 percent. Given that the RPI inflation rate is currently about 4.1 percent and rising, in real terms, we can, perhaps, expect house prices to fall somewhere between 7 to 8 percent this year.

This raises an interesting question; how long will the housing crash take? Suppose in rough terms, house prices are overvalued by 100 percent in terms of affordability and price to income ratios. Assuming that the combined nominal price fall and rate of inflation is around 8 percent, then it would take about 8 years for house prices to work off all that excess valuation.

So, homeowners, how do you feel about eight years of a "healthy price correction". Tough medicine, methinks.

So what happened in December? According to Hometrack, the average cost of a home in England and Wales fell by 0.3 percent. After 12 months of those kinds of monthly declines, prices would be down around 3.6 percent. Given that the RPI inflation rate is currently about 4.1 percent and rising, in real terms, we can, perhaps, expect house prices to fall somewhere between 7 to 8 percent this year.

This raises an interesting question; how long will the housing crash take? Suppose in rough terms, house prices are overvalued by 100 percent in terms of affordability and price to income ratios. Assuming that the combined nominal price fall and rate of inflation is around 8 percent, then it would take about 8 years for house prices to work off all that excess valuation.

So, homeowners, how do you feel about eight years of a "healthy price correction". Tough medicine, methinks.

Sunday, 27 January 2008

Stability destabilises

"In finance, to borrow from the economist Hyman Minsky, nothing is so destabilizing as stability. The paradox is easily explained. Profit-seeking people will take more financial risk when they believe the coast is clear. By taking bigger chances, however, they unwittingly make the world unsafe all over again.

Anxious people don’t ordinarily get in over their heads; it’s the confident ones who do. And nothing builds confidence like the belief that a greater power has conquered the business cycle and laid inflation low. In such happy circumstances, a calculating human will take out a bigger mortgage, build a bigger hedge fund or attempt a gaudier corporate buyout. That is, he or she will borrow more money, or, as they say on Wall Street, lay on more leverage."

James Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer

Anxious people don’t ordinarily get in over their heads; it’s the confident ones who do. And nothing builds confidence like the belief that a greater power has conquered the business cycle and laid inflation low. In such happy circumstances, a calculating human will take out a bigger mortgage, build a bigger hedge fund or attempt a gaudier corporate buyout. That is, he or she will borrow more money, or, as they say on Wall Street, lay on more leverage."

James Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer

Saturday, 26 January 2008

Deflation or inflation

In my most recent post which was on the possibility of major US investment bank failing, a reader - trader boy - left the following comment:

"do you read Mish?

if not, you should. it's becoming clear that DEFLATION is on the way. even the markets are telling you that, TIPS have not really done a lot for years, and long treasuries just hit all-time lows. that's not an inflationary sign."

On the first point, I will admit to reading Mish, but perhaps not as much as I should. I will, in future, rectify that failing.

However, trader boy has a second, more serious comment to make; whether the US, or the UK for that matter, will drift into a prolonged period of deflation rather than inflation.

His comments taps into a very difficult question, and I will admit to holding both opinions on different occasions. Nevertheless, I thought it might be useful to outline what I understand to be the two arguments, and why I think inflation, ongoing financial sector difficulties, and ultimately a recession are the most likely outcomes.

Deflation

Why would anyone think that after decades of inflation that prices might actually start to fall?

If inflation is due to an increase in the money supply, then deflation must be due to a decline. So why might Trader Boy and others think that the money supply might suddenly contract?

It is one of the great ironies of the modern world, but the vast majority of people do not have a clue how money is created. Of course, people understand that there are such things as central banks, and somewhere, the banks have printing presses that produce the notes they carry in their purses.

It is the role of commercial banks where the ignorance arises. It is the high street banks that generate the greater part of the money supply. The banks do this by creating loans while keeping only a small fraction of their assets in reserves as cash.

Central banks only determine short term interest rates, and in reality, have little control over commercial banks lending activities. In recent years, commercial banks made the most of their independence. They have created staggering amounts of money, largely through financing the real estate boom.

The commercial bank's money creating capacities are at the core of the deflationary argument, which in fact comes in two sizes; regular and supersize.

The regular deflation argument suggests that the banks, after years of feeding the housing frenzy are now chastened. Lending standards are tightening, and credit growth will be reduced. Without the performance enhancing flow of credit, the economy will slide into a recession, aggregate demand will fall, and inflation will abate. Banks may even become so cautious that credit growth grinds to a halt and with it, the money supply. This lack of monetary growth will eventually lead to prices falling.

The supersize version looks for a more dramatic and absolute decline in credit growth. Bank balance sheets, both in the UK and in the US, are fundamentally rotten. Those housing loans are about to go bad; defaults will rise, and when they do, banks will fail. The subsequent banking crisis will create a catastrophic collapse of balance sheets, credit will contract, and the money supply will fall. The consequences will be deflation and a depression very much along the lines of what happened in the United States in the 1930s.

Inflation

Given the events of the last six months, it is not hard to see why some people might think that deflation could be a possibility. The idea of a systemic banking crisis does not seem so far fetched; Northern Rock, sub prime, failing bond insurers, rising spreads and sporadic liquidity difficulties all attest to the growing weakness of the financial sector in both the UK and the US.

The problem, however, is that it is not just the US where we see a recent period of lax monetary policy. The world is full of money. From the tip of Africa to the top of Siberia, countries are loaded with unprecedented levels of foreign reserves, while their central banks have allowed very rapid monetary growth.

The cause of this worldwide explosion in monetary growth lies in an unspoken agreement between the US and emerging market economies. They agreed to supply cheap goods, and in return they accepted US dollars in exchange. Rather than spend these dollars on American goods, these dollars have been reinvested back into the US assets. This has kept US interest rates down, and allowed Americans to build up huge debts and keep on spending.

The deal has been good for emerging market economies, who have run up current account surpluses, and built up huge holdings of US assets, especially US treasury bills. Over the last ten years, these economies have enjoyed unprecedented growth and rising living standards.

These surpluses, if left to their own devices, should have prompted emerging market currencies to appreciate. However, emerging market central banks would not let that happen. They printed domestic money, in order to keep their exchange rates competitive. This kept the exports growing and allowed the US to keep their current account.

Unsurprisingly, these economies would like the deal to continue. Unfortunately, this implicit bargain was not sustainable, and today it is unwinding. It is inflation that is turning the screw. As emerging market economies have grown, commodity price inflation has increased; fuel and food inflation are rising rapidly, on account of higher living standards in places like China, Russia, India and the Middle East.

Inflation wins the day

Broadly speaking, there are three reasons why inflation and not deflation is the most likeliest outcome.

First, the Fed are again trying to use monetary policy to pump up demand. However, the recent interest rate reduction will serve to weaken the dollar, and as the dollar slides, import inflation will increase. Nor can we discount the possibility that all this excess liquidity might actually revive lending activity. It is unlikely, I agree, but Bernanke is a reckless inflator. He may bring rates down so far he could kick off another bubble somewhere.

Second, commodity price inflation is still rising. It is fueled by monetary growth in the rest of the world, which shows no signs of slowing. In many parts of the world, this monetary growth reflects a conscious decision to keep the US importing. Many key US trading partners, such as China and Japan, do not want to see a gradual reduction of the US current account. Although the dollar has fallen against the euro, the dollar has barely moved against Asian currencies. Many central banks continue to prevent their domestic currencies to appreciating against the dollar.

However, rising inflation will eventually prompt an adjustment, despite the best efforts of Asian central banks to prevent it. Furthermore, it will be our old friend, inflation, that will help the adjustment. Inflation in emerging markets is taking off, and as it does, real exchange rates will appreciate and this will eventually choke off export growth.

Finally, while recognizing the probability of a systemic banking crisis, it would need to be a truly massive one to generate deflation. Here, history is against the deflationary argument. The S&L crisis did not bring in its wake bring any deflation. The losses from sub prime have not yet reached the magnitude of that now almost forgotten crisis. While the sub prime crisis is big and nasty, it will need to get a whole lot bigger if it is to generate deflation.

So what are we looking at?

The situation today looks more like the 1970s than the 1930s. During the 1970s, the US ran up huge macroeconomic imbalances on account of the Vietnam war; it had a large current account deficit, an exploding fiscal deficit, and a weak and accommodating central bank, desperate to print money to avoid facing the consequences of a decade of bad policies. The dollar was tanking while the rest of the world had more dollars than they wanted. Does any of this sound familiar?

The US is looking at something very much in tune with the experiences of the 1970s - stagflation. It may have its very own 21st century flavour. For example, the growing banking sector difficulties may add a problem that was not evident back when Nixon was President. Nevertheless, the parallels are striking.

So I am with the inflation gang. Going forward, the US and UK economies will slow, but with inflationary pressures continuing. As unemployment increases, there will be some very limited downward pressure on domestic prices, but this will not be enough to counter the growing inflationary pressures coming world commodity prices. Moreover, those who remain in work will continue to push for higher wage increases.

As for deflation, the only market that will see falling prices will be real estate. In the case of the US, this has been going on for two years, while in the UK, prices have only just begun to slide. However, declining house prices can live quite happily with rapid inflation.

So, we are something of retro period in economics, but it is the 1970s and not the 1930s that are on the way back. Like Led Zeppelin, stagflation is on a comeback tour.

"do you read Mish?

if not, you should. it's becoming clear that DEFLATION is on the way. even the markets are telling you that, TIPS have not really done a lot for years, and long treasuries just hit all-time lows. that's not an inflationary sign."

On the first point, I will admit to reading Mish, but perhaps not as much as I should. I will, in future, rectify that failing.

However, trader boy has a second, more serious comment to make; whether the US, or the UK for that matter, will drift into a prolonged period of deflation rather than inflation.

His comments taps into a very difficult question, and I will admit to holding both opinions on different occasions. Nevertheless, I thought it might be useful to outline what I understand to be the two arguments, and why I think inflation, ongoing financial sector difficulties, and ultimately a recession are the most likely outcomes.

Deflation

Why would anyone think that after decades of inflation that prices might actually start to fall?

If inflation is due to an increase in the money supply, then deflation must be due to a decline. So why might Trader Boy and others think that the money supply might suddenly contract?

It is one of the great ironies of the modern world, but the vast majority of people do not have a clue how money is created. Of course, people understand that there are such things as central banks, and somewhere, the banks have printing presses that produce the notes they carry in their purses.

It is the role of commercial banks where the ignorance arises. It is the high street banks that generate the greater part of the money supply. The banks do this by creating loans while keeping only a small fraction of their assets in reserves as cash.

Central banks only determine short term interest rates, and in reality, have little control over commercial banks lending activities. In recent years, commercial banks made the most of their independence. They have created staggering amounts of money, largely through financing the real estate boom.

The commercial bank's money creating capacities are at the core of the deflationary argument, which in fact comes in two sizes; regular and supersize.

The regular deflation argument suggests that the banks, after years of feeding the housing frenzy are now chastened. Lending standards are tightening, and credit growth will be reduced. Without the performance enhancing flow of credit, the economy will slide into a recession, aggregate demand will fall, and inflation will abate. Banks may even become so cautious that credit growth grinds to a halt and with it, the money supply. This lack of monetary growth will eventually lead to prices falling.

The supersize version looks for a more dramatic and absolute decline in credit growth. Bank balance sheets, both in the UK and in the US, are fundamentally rotten. Those housing loans are about to go bad; defaults will rise, and when they do, banks will fail. The subsequent banking crisis will create a catastrophic collapse of balance sheets, credit will contract, and the money supply will fall. The consequences will be deflation and a depression very much along the lines of what happened in the United States in the 1930s.

Inflation

Given the events of the last six months, it is not hard to see why some people might think that deflation could be a possibility. The idea of a systemic banking crisis does not seem so far fetched; Northern Rock, sub prime, failing bond insurers, rising spreads and sporadic liquidity difficulties all attest to the growing weakness of the financial sector in both the UK and the US.

The problem, however, is that it is not just the US where we see a recent period of lax monetary policy. The world is full of money. From the tip of Africa to the top of Siberia, countries are loaded with unprecedented levels of foreign reserves, while their central banks have allowed very rapid monetary growth.

The cause of this worldwide explosion in monetary growth lies in an unspoken agreement between the US and emerging market economies. They agreed to supply cheap goods, and in return they accepted US dollars in exchange. Rather than spend these dollars on American goods, these dollars have been reinvested back into the US assets. This has kept US interest rates down, and allowed Americans to build up huge debts and keep on spending.

The deal has been good for emerging market economies, who have run up current account surpluses, and built up huge holdings of US assets, especially US treasury bills. Over the last ten years, these economies have enjoyed unprecedented growth and rising living standards.

These surpluses, if left to their own devices, should have prompted emerging market currencies to appreciate. However, emerging market central banks would not let that happen. They printed domestic money, in order to keep their exchange rates competitive. This kept the exports growing and allowed the US to keep their current account.

Unsurprisingly, these economies would like the deal to continue. Unfortunately, this implicit bargain was not sustainable, and today it is unwinding. It is inflation that is turning the screw. As emerging market economies have grown, commodity price inflation has increased; fuel and food inflation are rising rapidly, on account of higher living standards in places like China, Russia, India and the Middle East.

Inflation wins the day

Broadly speaking, there are three reasons why inflation and not deflation is the most likeliest outcome.

First, the Fed are again trying to use monetary policy to pump up demand. However, the recent interest rate reduction will serve to weaken the dollar, and as the dollar slides, import inflation will increase. Nor can we discount the possibility that all this excess liquidity might actually revive lending activity. It is unlikely, I agree, but Bernanke is a reckless inflator. He may bring rates down so far he could kick off another bubble somewhere.

Second, commodity price inflation is still rising. It is fueled by monetary growth in the rest of the world, which shows no signs of slowing. In many parts of the world, this monetary growth reflects a conscious decision to keep the US importing. Many key US trading partners, such as China and Japan, do not want to see a gradual reduction of the US current account. Although the dollar has fallen against the euro, the dollar has barely moved against Asian currencies. Many central banks continue to prevent their domestic currencies to appreciating against the dollar.

However, rising inflation will eventually prompt an adjustment, despite the best efforts of Asian central banks to prevent it. Furthermore, it will be our old friend, inflation, that will help the adjustment. Inflation in emerging markets is taking off, and as it does, real exchange rates will appreciate and this will eventually choke off export growth.

Finally, while recognizing the probability of a systemic banking crisis, it would need to be a truly massive one to generate deflation. Here, history is against the deflationary argument. The S&L crisis did not bring in its wake bring any deflation. The losses from sub prime have not yet reached the magnitude of that now almost forgotten crisis. While the sub prime crisis is big and nasty, it will need to get a whole lot bigger if it is to generate deflation.

So what are we looking at?

The situation today looks more like the 1970s than the 1930s. During the 1970s, the US ran up huge macroeconomic imbalances on account of the Vietnam war; it had a large current account deficit, an exploding fiscal deficit, and a weak and accommodating central bank, desperate to print money to avoid facing the consequences of a decade of bad policies. The dollar was tanking while the rest of the world had more dollars than they wanted. Does any of this sound familiar?

The US is looking at something very much in tune with the experiences of the 1970s - stagflation. It may have its very own 21st century flavour. For example, the growing banking sector difficulties may add a problem that was not evident back when Nixon was President. Nevertheless, the parallels are striking.

So I am with the inflation gang. Going forward, the US and UK economies will slow, but with inflationary pressures continuing. As unemployment increases, there will be some very limited downward pressure on domestic prices, but this will not be enough to counter the growing inflationary pressures coming world commodity prices. Moreover, those who remain in work will continue to push for higher wage increases.

As for deflation, the only market that will see falling prices will be real estate. In the case of the US, this has been going on for two years, while in the UK, prices have only just begun to slide. However, declining house prices can live quite happily with rapid inflation.

So, we are something of retro period in economics, but it is the 1970s and not the 1930s that are on the way back. Like Led Zeppelin, stagflation is on a comeback tour.

For the Fed, it is Merrill Lynch every time.

Over the last few weeks, a question has bugged me. Could the sub prime crisis bring down a major US investment bank? The crisis has already destroyed some 220 small financial institutions. It also forced Bank of America to bail out Countrywide, one of America's largest sub prime lenders. But what about a gorilla? Could it take down one of the big beasts roaming the financial jungle?

There are two badly wounded investment banks out there; Citigroup and Merrill Lynch. Out these two, Merrill looks the most vulnerable. In early January, the bank reported the worst quarter in its history, forcing the bank to write off $16 billion due to sub prime investments.

How much of a financial hit is $16 billion to a bank like Merrill? These days, balance sheets are available with a click of the mouse. Merrill started out in 2007 with assets amounting to $841 billion, and liabilities of $802 billion.

Subtracting assets from liabilities gives the bank's capital, which is the loss-making shock absorber. So long as the bank has a sufficiently large stock of capital, the bank can ride calamitous decisions like investing in sub prime assets. Simple arithmetic tells us that at the end of 2006, Merrill had capital amounting to around $39 billion.

The Merrill website has a couple of further, more interesting numbers for capital. During the first quarter, bank capital increased by around $2 billion, to around $41 billion. By the end of 2007, the bank had owned up to the losses. As a consequence, bank capital fell to $32 billion. In simple terms, sub prime investments burned up around 24 percent of Merrill's capital.

Looked from the perspective of bank capital, these losses are mighty. While subprime has not put the bank in any immediate danger of insolvency, neither is the bank in any shape to absorb any further shocks.

So when Bernanke met with the rest of the FOMC on Monday, he almost certainly had Merrill foremost in his mind. With the stock market crashing on monday, he had a vision of a further financial shock ripping through the banking system, zapping bank capital, much like the sub prime crisis did in 2007. He may be worried about a recession, but he is petrified of a major bank sinking into bankruptcy.

There is only one way he can help; reduce rates. This will allow banks like Merrill to increase their spreads between borrowing and lending money. Over time, bank profitability will improve and gradually bank capital will recover.

However, the rate cut comes at a time when inflationary pressure in the US is at a 17 year high. The CPI is now over 4 percent and will almost certainly rise further. After several years of relentless dollar weakness, import prices are rising.

However, when it comes to choice between Merrill or inflation, the Fed knows what to choose. It will be Merrill every time. This leads us to a profound conclusion. Whatever the Fed may say, monetary policy is there to serve Wall Street.

There are two badly wounded investment banks out there; Citigroup and Merrill Lynch. Out these two, Merrill looks the most vulnerable. In early January, the bank reported the worst quarter in its history, forcing the bank to write off $16 billion due to sub prime investments.

How much of a financial hit is $16 billion to a bank like Merrill? These days, balance sheets are available with a click of the mouse. Merrill started out in 2007 with assets amounting to $841 billion, and liabilities of $802 billion.

Subtracting assets from liabilities gives the bank's capital, which is the loss-making shock absorber. So long as the bank has a sufficiently large stock of capital, the bank can ride calamitous decisions like investing in sub prime assets. Simple arithmetic tells us that at the end of 2006, Merrill had capital amounting to around $39 billion.

The Merrill website has a couple of further, more interesting numbers for capital. During the first quarter, bank capital increased by around $2 billion, to around $41 billion. By the end of 2007, the bank had owned up to the losses. As a consequence, bank capital fell to $32 billion. In simple terms, sub prime investments burned up around 24 percent of Merrill's capital.

Looked from the perspective of bank capital, these losses are mighty. While subprime has not put the bank in any immediate danger of insolvency, neither is the bank in any shape to absorb any further shocks.

So when Bernanke met with the rest of the FOMC on Monday, he almost certainly had Merrill foremost in his mind. With the stock market crashing on monday, he had a vision of a further financial shock ripping through the banking system, zapping bank capital, much like the sub prime crisis did in 2007. He may be worried about a recession, but he is petrified of a major bank sinking into bankruptcy.

There is only one way he can help; reduce rates. This will allow banks like Merrill to increase their spreads between borrowing and lending money. Over time, bank profitability will improve and gradually bank capital will recover.

However, the rate cut comes at a time when inflationary pressure in the US is at a 17 year high. The CPI is now over 4 percent and will almost certainly rise further. After several years of relentless dollar weakness, import prices are rising.

However, when it comes to choice between Merrill or inflation, the Fed knows what to choose. It will be Merrill every time. This leads us to a profound conclusion. Whatever the Fed may say, monetary policy is there to serve Wall Street.

Quote of the day

"An annual review by Income Data Services showed that the median total earnings of the chief executives of the FTSE 100 companies - the UK's 100 largest quoted companies - in the financial year 2005/06 was £2m, up 20pc on the previous year.

By contrast, the gross median pay for full-time British employees in April 2006 was £23,600, up a mere 3pc on the previous year. So the typical FTSE 100 boss earned 75.2 times what the typical employee was paid - and just one year's pay rise for that typical boss was £400,000, equivalent to 17 times the total pay of the typical employee."

Robert Peston, Daily Telegraph

By contrast, the gross median pay for full-time British employees in April 2006 was £23,600, up a mere 3pc on the previous year. So the typical FTSE 100 boss earned 75.2 times what the typical employee was paid - and just one year's pay rise for that typical boss was £400,000, equivalent to 17 times the total pay of the typical employee."

Robert Peston, Daily Telegraph

Friday, 25 January 2008

Buy To Let heads south

"Buy to let investors will keep the South East the most prosperous area."

When I saw this title, I had to check the date. How could anyone write anything like this on the same day that also saw mortgage approvals fall almost 40 percent. However, the date was there - Thursday, January 24, 2008.

However, the article was even scarier than the title. According to a Homebuyer and Property investor survey, 70 percent of investors believe that the South east and London will be the top performing market this year. Furthermore, the article identified the "growth in buy-to-let interest in London and the South East" as the primary factor that "will help to buoy the UK property market."

The disconnect with reality didn't stop there. Around "40 per cent of investors" still considered new-built flats as "the most profitable buy-to-let investment."

So what accounts for all this unjustified optimism? "Supply and demand, improved transport links, wealth, foreign buyers and regeneration across the area".

Unfortunately for buy-to-let investors, none of their optimism is reflected in rental yields, which have in real terms, been flat for at least ten years.

When I saw this title, I had to check the date. How could anyone write anything like this on the same day that also saw mortgage approvals fall almost 40 percent. However, the date was there - Thursday, January 24, 2008.

However, the article was even scarier than the title. According to a Homebuyer and Property investor survey, 70 percent of investors believe that the South east and London will be the top performing market this year. Furthermore, the article identified the "growth in buy-to-let interest in London and the South East" as the primary factor that "will help to buoy the UK property market."

The disconnect with reality didn't stop there. Around "40 per cent of investors" still considered new-built flats as "the most profitable buy-to-let investment."

So what accounts for all this unjustified optimism? "Supply and demand, improved transport links, wealth, foreign buyers and regeneration across the area".

Unfortunately for buy-to-let investors, none of their optimism is reflected in rental yields, which have in real terms, been flat for at least ten years.

Quote of the day

"If it wasn't so strange, it wouldn't be true. So this guy, unbeknownst to Societe Generale, his employer, made £60 billion in bets on the Footsie and other indexes out there. Then this weekend he was found out, and the bank quickly sold off his positions, causing the markets to tank.

And like the planes hitting the towers gave Cheney what he needed, this charade was the perfect excuse for Bank Bailout Ben to hop into action, dropping rates a historical 3/4 point in an emergency cut."

Keith, Housing Panic

And like the planes hitting the towers gave Cheney what he needed, this charade was the perfect excuse for Bank Bailout Ben to hop into action, dropping rates a historical 3/4 point in an emergency cut."

Keith, Housing Panic

Reduce rates in haste; repent at your leisure

This week proved, if any proof were needed, that the Federal Reserve is run by clowns.

The week starts with a public holiday in America. But while Americans were honouring the memory of Martin Luther King, stock markets around the world were engaged in a major sell-off.

Coco Bernanke gets into the office early on Tuesday morning, he switches on his bloomberg terminal and sees a tidal wave of selling. Overcome by panic, he calls his fellow FOMC members and tells them that the US is on the brink of the greatest recession since the war. Only decisive action will do. So, the FOMC announces the biggest interest rate cut in 25 years.

Back over at the markets, the news of a 0.75 percent cut is greeted by a mixture of shock and incomprehension. In an efforts to explain the Fed's action, a consensus gradually emerges; perhaps the Fed knows more about a rapidly approaching recession. Perhaps, the FOMC had some advance warning of some shocking US macro data, pointing to the inevitability of a slowdown.

Shift forward two days and that interpretation of events looks extremely generous. France's second largest bank announces a $7 billion "fraud". Eventually, it emerged that this fraud is rather more like a huge trading loss than a criminal conspiracy.

As more details emerge, we find out that Societe Generale knew about the problem on Saturday, while on Monday, the beleaguered bank tried to unwind their exposure.

Suddenly, an entirely new explanation emerges. The sell off on Monday was almost certainly provoked by Societe Generale's desperate attempts to establish the extent of their losses before they announced their difficulties to the rest of the world. As Societe Generale were offloading their positions, others jumped in and started to sell.

Back over at the fed, it knew nothing of Societe Generale's difficulties. Instead, the Fed reacted with a mad and totally unjustified rate cut without any clue about that was actually happening within the world's financial markets.

The Fed is now trapped. It can not reverse this rate decision, since that would be an admission that it over-reacted on Tuesday. It is now stuck with an excessively expansionary monetary policy. It all goes to prove the Fed simply does not know what it is doing.

Thursday, 24 January 2008

I almost forgot to mention it; the UK housing market is crashing

With all this crazy stuff about rogue traders, sub-prime losses and manic interest rate cuts, the UK housing crash has drifted into the background. It is time to bring it out of the shadow; buried beneath today's shocking financial news, the British Bankers Association issued the latest data on mortgage approvals.

Now what is the right word to describe the latest data? The numbers were miles beyond "bad". They were well south of "appalling". In fact, there were found within the vicinity of catastrophic.

December mortgage approvals are down about 38 percent compared to 2006. Moreover, the actual number of approvals were the lowest since records began. Yes, that is right. Let us repeat that; mortgage approvals were the lowest since records began.

This brings us nicely to the golden rule of real estate; credit availability determines house price inflation. As today's data amply illustrates, credit availability has collapsed. As credit disappears, so does housing demand.

However, in one crucial respect the housing market is different from other markets. Normally, when demand falls, prices adjust downwards. With housing, people are notoriously reluctant to cut prices. Instead, volumes collapse. Don't look for the housing crash in estate agent's windows. It will take years before prices come down.

Instead, the crash will hit the financial services sector; no mortgages means a recession for building societies. Many estate agents will quickly downsize and disappear. While all that lovely lolly generated by stamp duty will evaporate. Yes, the chancellor will find slim pickings from housing.

As for home owners, they will suffer from an epidemic of denialitis. People may love their homes, but they love those inflated valuations even more. It will be hard to let go and recognize that house prices reached a high watermark in the early summer of 2007 and that those valuations will not return again for a generation.

Now what is the right word to describe the latest data? The numbers were miles beyond "bad". They were well south of "appalling". In fact, there were found within the vicinity of catastrophic.

December mortgage approvals are down about 38 percent compared to 2006. Moreover, the actual number of approvals were the lowest since records began. Yes, that is right. Let us repeat that; mortgage approvals were the lowest since records began.

This brings us nicely to the golden rule of real estate; credit availability determines house price inflation. As today's data amply illustrates, credit availability has collapsed. As credit disappears, so does housing demand.

However, in one crucial respect the housing market is different from other markets. Normally, when demand falls, prices adjust downwards. With housing, people are notoriously reluctant to cut prices. Instead, volumes collapse. Don't look for the housing crash in estate agent's windows. It will take years before prices come down.

Instead, the crash will hit the financial services sector; no mortgages means a recession for building societies. Many estate agents will quickly downsize and disappear. While all that lovely lolly generated by stamp duty will evaporate. Yes, the chancellor will find slim pickings from housing.

As for home owners, they will suffer from an epidemic of denialitis. People may love their homes, but they love those inflated valuations even more. It will be hard to let go and recognize that house prices reached a high watermark in the early summer of 2007 and that those valuations will not return again for a generation.

One more unemployed rogue trader

Société Générale €5bn trading loss finally answered a question that has bothered me for some time. What do you have to do to get fired from a bank without a big money pay-off? Jérome Kerviel - the rogue trader behind today's extraordinary losses, answered that question today. After nearly destroying the second largest bank in France, he has been "suspended pending a dismissal procedure".

Although subprime losses are in the tens of billions, surprisingly few people have been held to account. A handful of CEOs have been eased out, typically with massive golden handshakes, but apart from the hapless Mr "evil" Kerviel, I know of no cases of summary dismissals without compensation.

Therein lies are large part of the reason why we are in such a mess. This is rogue capitalism; huge rewards for reckless speculation; no consequences when things go wrong.

Although subprime losses are in the tens of billions, surprisingly few people have been held to account. A handful of CEOs have been eased out, typically with massive golden handshakes, but apart from the hapless Mr "evil" Kerviel, I know of no cases of summary dismissals without compensation.

Therein lies are large part of the reason why we are in such a mess. This is rogue capitalism; huge rewards for reckless speculation; no consequences when things go wrong.

Coco the clown

If the suit fits, wear it.

If the suit fits, wear it.Picture is courtesy of Adrian, who first posted it on the house price crash message board.

Quote of the day

"Nobody knows how big the losses are likely to be when the bottom is finally reached. And precisely because nobody knows, nobody wants to lend any more money. A rate cut won't change this. It's like offering a 10-pound lobster to someone so constipated he can't take in another mouthful."

Robert Reich, Former US Secretary of Labor and professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

Robert Reich, Former US Secretary of Labor and professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

Wednesday, 23 January 2008

Bernanke - you are on your own, mate

A day after the big fed cut, and the message from other central banks has been as clear as crystal - Bernanke is on his own.

No other central bank is likely to follow with a headline hitting uber-cut. While other banks might be contemplating a rate reduction, moderation will be the order of the day. Inflation may be only a marginal issue for the Fed, but other central banks continue to be concerned about rising price pressures.

Here in the UK, King went to Bristol where he gave his own account of recent developments. The speech is well worth a read. Although it has a rather dubious sea-faring theme running through it, the message is stark; "this year we (i.e. the UK) are probably facing a period of above-target inflation and a marked slowing in growth”. No talk of avoiding recessions for the Bank of England.

In contrast to Bernanke, King does not claim to have any Harry Potter-like magic potion hiding up his cape. "We (the Bank of England) have little control over the strength of the economic winds buffeting our economy. We cannot avoid some volatility in the short run and it is important that everyone understands the limits to the ability of central banks to smooth the economy."

Over at the ECB, one finds a similar realism about the limits of central banks. Earlier this week, Jürgen Stark, a member of the Executive Board of the ECB provided a straight talking assessment about how far central banks can influence economic growth. His assessment is worth quoting at length.

"Any attempt by central banks to systematically stimulate output and employment is ultimately doomed to failure, the only certain outcome being inflation. The perceived trade-off between inflation and growth will, sooner or later, reveal its true nature. Although it is tempting to believe that such a trade-off exists, it is in fact a mirage.

New empirical evidence and new insights in monetary theory have shown that even moderate levels of inflation have considerable negative repercussions for long-term economic performance, and maintaining price stability is therefore the best contribution that monetary policy can make to economic welfare, growth and employment."

Unfortunately, Bernanke and his fellow inflationist friends on the FOMC believe that a dramatic gesture and easy money will somehow save the day. However, the US macroeconomic imbalances are simply large. A further round of easy money will not reduce the burgeoning current account deficit, it will only exacerbate inflation, and it will not improve bank lending standards.

Although the Bank of England and the ECB have in the past made some terrible mistakes, neither central bank are quite so stupid as to believe that the answer to today's problem is a massive interest rate cut. Nor do they believe that the answer to a credit-induced asset bubble is yet more easy credit.

No other central bank is likely to follow with a headline hitting uber-cut. While other banks might be contemplating a rate reduction, moderation will be the order of the day. Inflation may be only a marginal issue for the Fed, but other central banks continue to be concerned about rising price pressures.

Here in the UK, King went to Bristol where he gave his own account of recent developments. The speech is well worth a read. Although it has a rather dubious sea-faring theme running through it, the message is stark; "this year we (i.e. the UK) are probably facing a period of above-target inflation and a marked slowing in growth”. No talk of avoiding recessions for the Bank of England.

In contrast to Bernanke, King does not claim to have any Harry Potter-like magic potion hiding up his cape. "We (the Bank of England) have little control over the strength of the economic winds buffeting our economy. We cannot avoid some volatility in the short run and it is important that everyone understands the limits to the ability of central banks to smooth the economy."

Over at the ECB, one finds a similar realism about the limits of central banks. Earlier this week, Jürgen Stark, a member of the Executive Board of the ECB provided a straight talking assessment about how far central banks can influence economic growth. His assessment is worth quoting at length.

"Any attempt by central banks to systematically stimulate output and employment is ultimately doomed to failure, the only certain outcome being inflation. The perceived trade-off between inflation and growth will, sooner or later, reveal its true nature. Although it is tempting to believe that such a trade-off exists, it is in fact a mirage.

New empirical evidence and new insights in monetary theory have shown that even moderate levels of inflation have considerable negative repercussions for long-term economic performance, and maintaining price stability is therefore the best contribution that monetary policy can make to economic welfare, growth and employment."

Unfortunately, Bernanke and his fellow inflationist friends on the FOMC believe that a dramatic gesture and easy money will somehow save the day. However, the US macroeconomic imbalances are simply large. A further round of easy money will not reduce the burgeoning current account deficit, it will only exacerbate inflation, and it will not improve bank lending standards.

Although the Bank of England and the ECB have in the past made some terrible mistakes, neither central bank are quite so stupid as to believe that the answer to today's problem is a massive interest rate cut. Nor do they believe that the answer to a credit-induced asset bubble is yet more easy credit.

Quote of the day

I picked this quote up from the big picture blog:

"It's a sad testament to think the Fed has to cut interest rates eight days in front of a meeting to salvage the equity markets. The U.S. economy is in a rather sad state of affairs in that it depends on housing and stock prices to keep going."

Bill Gross, founder and chief investment officer, Pacific Investment Management Co. (PIMCO)

The quote does have a certain sad logic.

"It's a sad testament to think the Fed has to cut interest rates eight days in front of a meeting to salvage the equity markets. The U.S. economy is in a rather sad state of affairs in that it depends on housing and stock prices to keep going."

Bill Gross, founder and chief investment officer, Pacific Investment Management Co. (PIMCO)

The quote does have a certain sad logic.

Tuesday, 22 January 2008

clowning around

It is highly doubtful whether anything good can come from Bernanke acting like a clown at a children's party, jumping out of a wardrobe waving his surprise 75 basis point interest rate cut.

The initial reaction will almost certainly be shock "What??? They cut by how much??" However, after a few minutes of reflection, a second more dangerous thought takes hold. Perhaps, the US economy is diving into a deeper recession than originally thought. After all, why does the Fed feel the need to cut so aggressively? Shock will be quickly replaced by concern.

Looking beyond a 24 hour horizon, it is hard to see how this cut could help much. Adjusted for inflation, fed rates are now negative. US inflation is accelerating, and reducing rates can only weaken the dollar, which is not exactly a recipe from price stability

The Fed appears to be, for all practical purposes, unconcerned about inflation. This will ultimately begin to affect inflationary expectations. Over the longer term, the Fed could be reviving the reputation it had from the 1970s. When it come to inflation, the Fed is a weak and accommodating central bank.

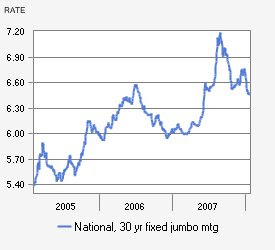

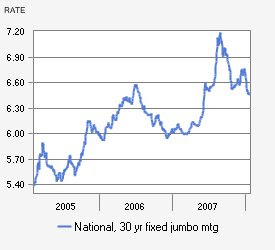

Although the Fed's amateur dramatics will grab headlines, the US housing market is extremely unlikely to benefit much from this cut. According to bankrate.com, the 30 fixed rate jumbo mortgage interest rate is 6.5 percent, which is approximately the same level it was at in mid-2007. After record sub-prime losses, US banks have significantly tightened their lending criteria. The days of easy mortgage credit are gone and will not return any time soon.

Likewise, consumer credit is unlikely become cheaper either. This largely reflects a growing concern about the capacity of US consumers to repay their loans. Banks are anxious to reduce exposure, while Wall Street isn't in any shape to repackage this debt and lift it from bank balance sheets. Currently, credit card rates average between 10-14 percent. These are not the type of rates that would encourage a recession-avoiding spending spree.

This recession was booked and paid for three years ago. The US housing bubble created massive macroeconomic imbalances that could only be resolved by an economic slowdown. Rising inflation has eroded the incentive to save. Personal household balance sheets are overloaded with debt. The current account deficit is unsustainable. Lending standards have been too lax, and pushed the financial sector to the brink of crisis. Another round of easy fed money does nothing to solve these problems.

It would have been better if the clown had remained in the wardrobe.